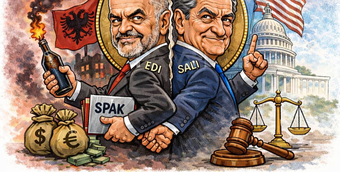

83 mandates are not immunity for Rama's friends

Edi Rama's reaction to SPAK's request to lift the immunity of Deputy Prime Minister Belinda Balluku is not simply an "X" status. It is an X-ray of the way he understands power, justice and his relationship with responsibility. And what appears in this political radiography is very simple. A prime minister who hides behind 83 mandates to avoid the fundamental question, does the law apply equally to everyone or not?

Rama begins by referring to the Constitutional Court's decision to suspend Balluku, as a decision that branded SPAK as "anti-inquiry and anti-democratic". But the Constitutional Court has not judged Balluku's guilt or innocence, it has judged the procedure for suspension from office. Using this decision as a stick to beat SPAK over the head is a very subtle way to delegitimize the investigation.

The prime minister then talks about “arrests without trial”, about a “rude fashion” of detentions, even bringing up the concerns of the Council of Europe. Rhetoric familiar to someone who has double standards, because when justice affects others, it is a historic reform; when it approaches your most powerful officials, it becomes a “dangerous fashion” and a threat to democracy. The problem is that security measures (prison, house arrest, etc.) are not decided by SPAK, but by the court. SPAK requests it, the court decides. Calling them “arrests without trial” means not accepting the very logic of criminal procedure in a state governed by the rule of law, especially when, until SPAK brought out its many “champions”, now defendants, it appeared as its lover.

Then comes the key sentence: “We will engage with all our responsibility before the Albanians who gave us 83 mandates…”. Where the number of mandates is used as a political argument to evaluate a criminal request. As if the majority in the Assembly were a judicial body that weighs evidence, testimonies, and expertise.

The Parliament in this case is not a court. It does not read the files, does not question witnesses, does not conduct a criminal investigation. It simply decides: can a member of the government be treated like any other citizen before the law, or not. Any talk of a “political stance” on the SPAK request is, in fact, an admission that Rama is giving himself the role of the government’s lawyer, not the state’s guardian.

Rama talks about “European democratic standards” and the number of detainees. But in no serious European country would it be normal for the prime minister to publicly suggest that a prosecutor “should not” request security measures for a member of the government, otherwise he is endangering democracy with its basic principle, the separation of powers. On the contrary, in any mature democracy, the moment when justice knocks on the doors of power is the greatest test of democratic standards. Not when former officials are investigated, but when the current government is at stake.

In the end, the battle is neither Balluk's nor a particular prosecutor's. It is a battle between two visions of the state, in one, the political power uses parliament as a shield to obstruct justice; in the other, the parliamentary majority accepts that its political legitimacy can never be turned into criminal immunity for the government. The more Rama hides behind 83 mandates, the clearer it becomes that the real problem today is not the severity of SPAK, but the fatigue, exhaustion and fear of a power that no longer knows how to coexist with accountability for corruption in every office of this power.

In this reality, Rama has only two possible answers to the public: either he knew nothing about the corruption that was going on around him, or he knew and tolerated it. In the first case, he is incapable of protecting the public interest; in the second, he is complicit, at least politically and morally. In both cases, the conclusion is the same, unfit to govern.

Happening now...

ideas

Hasimja kërkon të

For the reform parties, the government and the opposition

top

Alfa recipes

TRENDING

services

- POLICE129

- STREET POLICE126

- AMBULANCE112

- FIREFIGHTER128