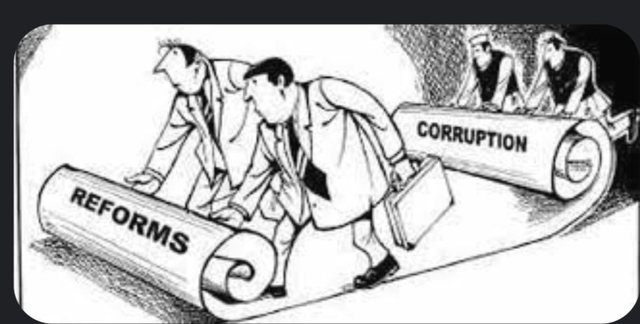

The phenomenon of corruption a losing battle!?

Thomas Carothers, Steven Levitsky, Lucan Way defend the thesis that hybrid regimes operate in an intermediate zone between democracy and authoritarianism, where corruption is structural and not accidental. Hybrid regimes use the tools of corruption as part of strategies for political stability. Instead of limiting corruption, governments often feed and distribute it deliberately, building clientelistic and patrimonialist networks that guarantee the loyalty of elites and the dependence of citizens.

On the other hand, the public also feeds and reproduces it from below, transforming it into an everyday and normalized value system. This, in many cases, leads to the internalization of corruption as a norm, where the citizen himself becomes an actor in the capture of the state, feeding clientelistic networks from the bottom up. In this context, instead of seeking reforms, individuals prefer to become part of a game where “the winner is not the one who respects the rules, but the one who knows how to circumvent them”.

This, the authors above state, is the most dangerous form of corruption, because it does not stem only from power, i.e. from the top down, but from the way an entire society conceives of justice, opportunity and dignity, i.e. from the bottom up.

This is precisely what has happened in Albania in recent years, as there is no way to explain some of the facts listed below that stem from reports, surveys or studies conducted on the phenomenon of corruption in Albania.

First, in the last five years, the perception of corruption in Albania, according to the Transparency International (CPI) index, has improved by only one point – from 35 to 36. In this context, the government is not simply an actor that tolerates corruption due to incompetence or institutional weakness, on the contrary, it often feeds, manages and distributes it deliberately, in order to build political alliances and ensure the stability of the system. Many scholars argue that governments in hybrid regimes such as Albania use corruption as a tool of patronage and clientelism, where loyalty to the government is rewarded with access to public funds, state contracts, employment, and other benefits. In this way, corruption becomes the currency of political circulation, where elites rely not on democratic legitimacy, but on mutual benefit and control of public resources.

Secondly, in the last five years, the perception of corruption in Albania by citizens has changed by very few points. This data raises more questions than it answers. First, a change of one point referred to the Transparency International (CPI) index shows that citizens’ trust in the fight against corruption remains low. Second, despite political rhetoric, legal initiatives and the creation of new institutions (such as SPAK or BKH), public perception has not changed significantly. This may mean that the reforms undertaken have been perceived more as technical or oriented by international pressure, and not as related to real change in the daily lives of citizens. Third, the minimal movement of one point raises doubts about the efficiency of the new justice system, which in theory was built to fight high-level corruption.

Third, surveys show a high level of perception of corruption by citizens, but when they are asked which political force is more corrupt, they line up more according to political beliefs than to a cold analysis of corruption indicators. This is a classic symptom of the excessive politicization of society, where party division supersedes critical analysis. Every scandal, regardless of the evidence, is interpreted through the lens of political loyalty, and not through the demand for accountability. This brings about a chain effect by increasing tolerance for corruption in the party that prefers it, as well as delegitimizing accusations against opponents by treating them as “political attacks.” In this terrain, accountability loses its meaning, because it becomes the object of propaganda and not of impartial judgment. Essentially, this situation is not simply a product of political polarization, but evidence of the failure to build a civic culture that puts the public interest above ideological loyalty. When citizens fail to separate fact from belief, corruption does not need to be hidden, it survives because everyone justifies it – each for "their own".

Finally, every survey shows that citizens have more trust in the fight against corruption in internationals than in local institutions in Albania. The role of internationals is overestimated compared to local ones, while only the latter can change the situation. This overestimation of internationals, although understandable, creates a double danger. First, it feeds civic passivity, reinforcing the idea that change does not come from within, but “others bring it to us”. Second, it reduces the pressure on local institutions to act and reform from within. In reality, no sustainable reform can come from outside, as long as local institutions do not adopt change as their own process and as long as citizens do not see themselves as active parts of democratic control. The solution is not to give up on international aid, but to gradually shift hope and action towards local institutions, through strengthening transparency, effective punishment and building a more accountable political culture.

In conclusion, we can say that corruption in contexts like ours is not simply a deviation from the norm, but the norm itself. It is systemic, that is, structurally intertwined with the way the state, politics, and society function. As such, it cannot be fought with partial measures, but requires a comprehensive transformation of the political and institutional system. As Mungiu-Pippidi points out, a society becomes “corruption-free” not when it punishes the corrupt from time to time, but when it shifts the balance between informal norms and formal rules – making corrupt behavior illogical, not just illegal.

The Ukraine summit that ignored the tough questions

ideas

top

Alfa recipes

TRENDING

services

- POLICE129

- STREET POLICE126

- AMBULANCE112

- FIREFIGHTER128